I grew up in the midwest. The public school system at the time was really great. I got to learn Earth Science from one of the most passionate teachers to exist in the field. I remember he inspired me to want to get to know the night sky and become familiar with how the earth formed. He was so passionate that he patented his own star chart, and even built a miniature planetarium, which was big enough to fit an entire classroom full of kids, out of black plastic and pinpricks. We all crawled in and amazed at how accurate it was.

This was my freshman year in high school. I was 14 years old, and I remember this being the first time I realized I had a hard time reconciling what I believed from church and what I was being presented with in school. The ideas did not match up. How could Adam be the first man if we evolved from apes? Why wasn’t evolution mentioned in the scriptures? Why aren’t church leaders talking about it?

I struggled with this for decades. I felt like I had to keep my religion in one pocket and my education and learning in the other. I did do that for such a long time. Then everything changed when I ran across a short video by a man called Stephen Meyer. In it, he indicated that there was an event called the Cambrian Explosion. If you’re not aware, the Cambrian explosion is a sudden appearance of many new species in the fossil record that don’t appear to have any evolutionary ancestors. This is something that can’t be explained by the geologic and evolutionary model that is taught in school.

What’s more is that Meyer goes on to explain that the origin of life itself is something that is so astronomically improbable so as to border on the absolute impossible.

The argument goes like this: If you are playing roulette, the ball could only land on black 16 so many times before you would start to question whether the roulette wheel was rigged somehow, and this is based solely on a 1/100 chance. This is something we would all intuitively accept for any other chance encounter with luck and/or odds. If a poker dealer drew a royal flush even once, any player would probably want to accuse that dealer of cheating. The odds of drawing a royal flush is 1/649,739.

Getting black 16 several times in a row or drawing a royal flush are long odds, but they are nothing compared to the probabalistic burden of randomly assembling a protein chain. Aside from the mechanical difficulties involved (which are great), assembling the correct sequence of As Cs Ts, and Gs to build a body plan by chance is so mind-bogglingly improbable that we have to resort to cosmic metaphors to bring it down to where we can conceive of it.

Let me explain: Say I want to express an idea in binary. If that idea is “2”, I can express it with two “letters,” “1” and “0” like this:

10

That sequence could represent a genome which is two “letters” long. So to fill the spaces of the “word,” I might have four tiles, two zeroes and two ones, that could potentially fill in the sequence. By this logic, I would have 22 = 4 permutations to fill in the sequence like this:

00

01

10 <— Correct answer

11

So, given a random encounter with the tiles, I would have a 25% chance of assembling the right sequence.

Now, if I want to express a much larger number, I will need more letters. Say I want to express the number “1776,” I will need more tiles. Turns out that number looks like this in binary:

11011110000

so I will need 11 tiles to represent that number. So, there are 211 ways those tiles can be permuted to render a different order. 211 is 2048. So if I had 22 tiles, I would have a 1/2048 chance or 0.48% probability of assembling them correctly to get the number I want. Even with a sequence that has only 11 “letters” and a “base pair” that is only 1 “letter” wide, this is already sounding impossibly improbable.

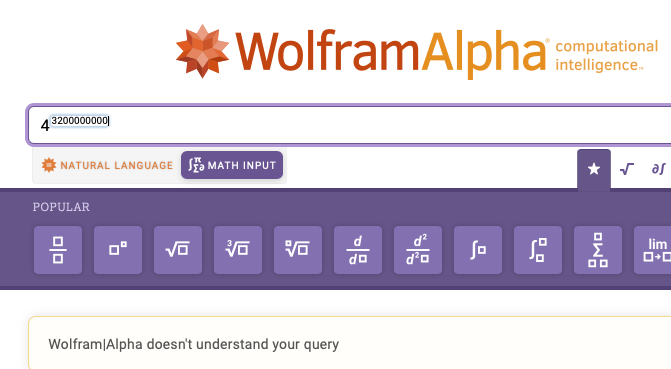

According to National Institude of General Medical Sciences, the human genome totally dwarfs these examples with 3.2 BILLION (with a B) base pairs. Additionally, each “letter” in the sequence has 4 possible values. So instead of a “1” or a “0”, I now get to choose “A”, “C”, “T” or “G”. This means that instead of 23.2 billion it’s now 43.2 billion. That number is gigantic. I tried to plug that number into wolfram alpha and got back Wolfram|Alpha doesn't understand your query

Just for fun, I took one of the zeroes off, so we’re only calculating 43.2 million. On wolfram, that number still yields a ridiculously huge amount:

~1.67 × 10192,659,197

That number is mind-bogglingly huge, you guys. Just for comparison’s sake, the number of particles in the universe (according to Popular Mechanics) is

3.28 x 1080

Look at those two numbers. They are not even in the same sphere of understanding. Meyer put a really fine point on it when he used a metaphor of an astronaut dropped in the middle of the milky way. If you were that astronaut, you’d have a better chance of finding a marked proton in the vast pile of particles all throughout all the galaxies of the observable universe than you would to “randomly” assemble a human genome by adding energy and time to the same matter.

What’s more, in this example, I am beginning with the conclusion I want in mind. I have a specific number I want, then each time I “draw” a tile, I can check to see if I have the right number. Evolution does not have this luxury. The only “check” it has is whether the genome can be passed on to the next generation in the organism’s offspring, so the problem is even more difficult because there are going to be a lot of failures with each “draw” of the tile because that tile might not even get to be placed in the sequence either because the organism is sterile, or because the organism didn’t reproduce before death caught up with it.

No other time in our lives do we approach such structured and ordered data and assume it assembled this way by chance. We would never stumble across a book we found on a beach and exclaim, “Oh! Look what a marvelous thing nature has produced through erosion!” We would immediately be looking for the author of such a book. Why don’t we do this with DNA?

I cannot begin to overstate or relate to you how much of a paradigm shift this was for me. I went and read Stephen Meyer’s book “Darwin’s Doubt” as well as a few of his other books. It felt like Meyer had handed me a chest full of shining diamonds. I had always hoped that “religion” and “science” could one day reconcile with one another and become one like in a marriage. Meyer opened this door for me. After I had read a few of his books, I found out that there are others who share this same doubt in Darwin’s research. Michael Behe is among them. Both of these gentlemen have written multiple books about this subject and have concluded that DNA does not fit the model of our understanding about evolution.

The research by these gentlemen and others have shaken the foundation of my secular understanding of the history of the earth, and it led me to an important epistemological discovery: our beliefs live and die with the assumptions they’re based on. I had assumed that what I was taught in school was the truth. It turns out that the truth is much harder to nail down–especially when you start digging through the ancient past. But what I had read in these books is backed by years of research, as I had assumed what I learned in school was, also. So now I have conflicting ideas that forced me to question the original assumption.

This is just one of the assumption-shaking questions that have helped shape my faith-journey. Which assumptions do your beliefs rely on?